No Man’s Land

Words and Images by Ryan Youngblood

“Yala!” The Arabic imperative is quietly shouted from a tall, thin man as he pushes the rest forward. His shoulders slack and struggle as his hands groove into something that sits on either side of his neck and curves beyond his body like a lion’s front teeth. Eight men adorned in rags and sandals snake through a suffocatingly dense forest at night. They hide from the moon as it flickers through the canopy. The moon, eternally cast to the sky each evening to search the forest floor for the thieves of earth’s possessions, a spotlight and the eye of night that watches in terror the unnatural taking of life; deaf and mute and unable to speak of the horror, so it gives light. In sorrow it offers a pale glow and it hides at the end of each watch to give the stronger sun its chance. The men live in a nocturnal world of crime. Fires are small and brief, the kind sat around in taut silence, eating rice bathed in palm oil and waiting for one’s turn to watch over camp. They step into canary clearings, holes under the tree tops and they look up like from the bottom of a well. Their enemy follows the stars and can see at night from high above. However, the modernity of weapons are an ironic un-matching of foes when compared to the men’s knowledge and experience of the forest. An orchestra of sounds follow the men, thuds from the freshly cut elephant tusks living on the man’s shoulders, grunts of fatigue, and the jingling of bullets from an armory of black market weapons. The wet season in the Central African Republic(CAR) is an attack from above and below, with the grass reaching over eight feet and the rain pelting like petrified hail. The elephant poachers would have given up much earlier, or never have came, if the price per kilo on ivory wasn’t $2000. They’re only middle men, opportunists, desperate and poor, contracted killers that see very little of the payout. They reach the end of the tree line and the moon’s shine reflects cold tones of blood off each man’s black skin. They continue and move across the CAR-Sudan border, a mirage of a line that is pushed, pulled or vanished every day. The forest’s shadow takes them in again as fingers hug triggers and the blinding void of its aphotic center consumes them and their sight.

The reverie vanished and I was back in the morning, its blue and gray overcast sombering the day as I slid across my foam pad in jungle sweat. I headed for the fire out of my one man tactical tent. Every morning was spent eating gozo, a gooey like mashed potato made from cassava root tubers and dipped in okra sauce. I chased a few Benadryl with black coffee to temper a swollen forearm from multiple bee stings, city slicker allergies that always flare in the bush. 19 days into a 38 day mission, and I wondered how I got here. My mind drifted to a year prior in an old haunt in Kampala, Uganda. Afro pop reverberated through static speakers, and Chinese made neon disco balls threw dots of light over every floor and wall of the bar. Hookers in the corners and loud men in chairs, billowing plates of nyoma choma and liter bottles of beer hung onto the edges of their plastic tables. I was with a friend drinking a Nile lager as we rapped about African ethnic heritage and its history of settlement, tribal cultural differences, corrupt and unstable governments, former and current colonial suppression, foreign interests and exploitation, and the implications of these issues for the continent and the world. Small talk. We questioned what was left, what was truly undiscovered in Africa. He leaned in almost to conceal his words and spoke of such a place. He unfolded a serviette and drew the outline of the CAR, lightly shading an area in the north east of the sketch. Time seemed to reverse and we were like the old explorers, speaking of rumored treasure, lost civilizations, and uncharted swathes of land that don’t exist on modern maps. His eyes grew with excitement and almost appeared haunted by the knowledge. This area felt mythological, an isolated Eden surrounded by threats that kept it locked away in the center of Africa. He pulled out his moleskin and thumbed to the back - Erik Mararv / Cawa Safaris - ripping out the page he buried it into my palm. Erik became my Livingstone and how I’d find myself in The Central African Republic. The CAR is a former French colony bordering Chad, The Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, and Cameroon. Post independence was followed by a sequence of appointed autocrats and then eventual democracy with overt corruption and special interests. And in the shaded corner of the country was 17,600 square kilometers known as the Chinko River Basin (Chinko). Communities border it, but otherwise Chinko has no permanent settlements. The ecosystem is an interconnected flow of Congolian tropical rainforests and Sahelian savannas, making it one of the most biodiverse and important habitats in Africa. A mosaic of thick trees and jungle collide into shrubs and barren ground, then is cut through by the curving Mbari River for 71 kilometers. The treetops are a microcosm of primates with their own life and culture, 10 different species engaging in trade, war, and love. And below, forest and savanna elephants and buffalo co-exist, crossing from their evolutional habitat into unselected biomes more fit for their neighboring sub-genus. The remaining hooved animals and carnivores share the same narrative and it’s what makes Chinko an ecological paradise.

Mararv, a nordic surname akin to fair skin, blue eyes and an unidentifiable accent. Erik was ‘Mararv’, a pure Swede, but only his outer self. Everything else inside was African, a wild spirit raised on his father’s back tracking bull elephant through blade sharp and bamboo high grass. His French was perfect and his Sango, the language of CAR, even better. He dreamt of starting a hunting outfit in the CAR, neither Quixotic in his dreams nor narrow in his vision, he was truly African and knew his land and knew his people; thus he made his dream come true. And eventually mine because it was Erik’s fabled hunting company that tethered me closer to the Central African Republic. In Africa, trade is still enterprise and bartering still an art, so like in a market we agreed upon ‘hunting for pictures’. I could never have known, but Erik was corresponding from prison. Himself and a colleague had been framed for murder, and as outrageous a claim, it was an easy pin to throw on a white man in the aforementioned context of a post-colonial corrupt nation. He found 13 dead bodies bound by their wrists and ankles. The men were gold miners and had been killed by LRA combatants. The Lord Resistance Army, an active rebel group in the CAR, found spiritual purpose in how they took life and it became an art and a process that was never over-sighted. The victims had their genitals removed and sticks balancing in their throats as their heads scowled at the earth in a silent scream. Witch craft, christendom and divine appointment all boiled into a spell of evil that ran through the dark blood of the LRA. And so they could kill without conscious. Erik was eventually released of the charges and found me on the Chinko airstrip looking for him.

Chinko was a thriving civilization and a hidden world, but perhaps more, a perfect and unintentional study of ‘man’. Men find worth, pleasure, and purpose in elemental things. The male design unbridled and unburdened by women and domestic illusion, we return to a primitive being, one that hunts for prize[that’s more man], and one that hunts to sustain[that’s more animal], and one that kills in war[that’s a bit of both]. ‘Men are born for games. Nothing else. Every child knows that play is nobler than work. He knows too that the worth or merit of a game is not inherent in the game itself but rather in the value of that which is put at hazard’. Erik and his hunting company, CAWA Safaris, were the foundation, the soil that in the wet or dry season could host an ambitious cadre of primordial ‘man’. CAWA Safaris attracted hunters from every end of the earth. Small town America, the French, Russians, and Arabs, they all gathered in the settlements built against the forest, a babel of posh huts and dining halls, and everyone speaking an English lingua franca, but muttering in their respective tongues. CAR is a place that chooses hunters. East and South Africa’s iconic sunsets or fields of wild game are inexhaustible, however, men still choose to cross the trails of threats that begin upon landing in CAR’s capital. At the time, an ongoing, and in its simplest form, sectarian war raged in Bangui, the capital sitting along the Ubangi River which separates the Central African Republic and The Congo. Hunters arrive and pass through a French military controlled airport. Street skirmishes and close contact fighting could be heard like distant roman candles and fire flowers. The men continue to a chartered Cessna 206 as they fly over the cinder and smoke that rises from the city asphalt. The plane lands on Chinko’s dirt runway and the men meet for the first time the middle of nowhere. Despite Chinko’s isolation, it was far from being alone. African soldiers in fatigues are seen shuffling between barracks and across the runway. Bangui’s war never reached Chinko, however another had. The LRA are a ghost and shape shifter that has evaded and maintained survival for over 20 years. They came from Uganda, orphaning villages by systematic kidnappings and forcing little boys to fight. Girls are less than objects and become wives to husbands in a matrimony of rape. The fight lasted in northern Uganda for two decades; however, since 2008 they’ve been pushed into Central Africa’s thick cover. Only so often will the LRA come up for air out of the forest, yet even then their cagey nature offers little window of opportunity for counter attack. The Ugandan military (UPDF) were deployed in CAR in a show of commitment, along with Obama ordered US spec-ops advising on tactic. The Chinko airstrip oscillated between 206’s, Mi-17’s, and CV-22 Osprey’s. CAWA Safaris agreed to share the runway as well as intelligence. Hunters and their trackers would occasionally come across former LRA camps, iconic sites cleared of brush with smoldering ash and a uniform line of Wellington boots disappearing into the forest. The trees had etched foot holds climbing the sides for lookouts to keep watch. On the ground, small, square plastic bags empty of 10 cent whiskey stolen from village raids, cylinder tins of Nido, and miniature jerry cans once full of palm wine. It was an oblige to Erik to keep the UPDF, yet it also benefited his war, another proxy war that shared an enemy with the UPDF and a second enemy that came even further and for something different than LRA asylum.

Chinko was at the headwaters of an ivory black market. Heavily armed poaching units from Sudan come in undetected packs, sometimes traveling by horseback like medieval knights, a fantasy looking fever dream from hell if ever seen in person. They’re highly motivated and battle hardened. The profits from ivory either filling pockets to supply an Asian demand or for fueling terrorist organizations’ fanatical missions. The pressured elephants coiled and lowed their giant bodies into the tightest spaces in Chinko, seeking harbor from the passing calvary. Erik’s arrangement with the UPDF would afford valuable information on the Sudanese movements. The Ugandan’s patrols would in the same mission encounter poaching camps, fresh with the air smelling of spooked men, their fires abandoned and dried ropes of meat hanging over tree limbs. Erik used CAWA as the parent to his newly formed conservation company, The Chinko Project; a team of biologists and ex-military to either study the wildlife or train rangers. His hunting maintained a value around the animals and it helped subsidize his conservation and anti-poaching operations. In an unfortunate coalition, the LRA joined the Sudanese in the ivory slaughter and soon the UPDF and Erik shared the same enemies. An equally effective adversary, yet less malicious in its purpose, were the Mbororo. The Mbroro are semi-nomadic Islamic pastoralists that take their families across the Sahel from Sudan in search for better grazing grounds. The land they come from is ashen from civil war and drought. There is nothing left for them in Sudan. Instead they must lead a nomadic life to graze their cattle in a greener Chinko and turn what they kill into a commodity for the market. The Mbororo will enter Chinko with AK’s and pepper rounds into large herds, unsustainably killing animals for bushmeat. Their cattle infect the area with foreign diseases, creating silent epidemics of the wildlife. And to protect their currency from predators they poison meat along their route for unlucky lions and leopards. The Mbororo are survivors and their plight meets Chinko with an unfortunate encounter. A 1,000 kilometer walk into Central Africa and poaching bushmeat is no more of a risk than staying at home surrounded by the beasts that civil wars create. Erik and his team recognized the historical significance of Chinko’s passage for the Mbororo. They could argue their presence long before the military and the hunters, however, Chinko couldn’t offer anymore what the Mbororo needed.

The fog of the morning lifted and the sun burnt through what remained. In Central Africa, 8am is a noon heat and you’re moving well before 6. Erik slipped through the thick brush, guiding myself and two trackers as his gait increased at each clearing. My arm was returning to its normal shape and Erik was fixed on eland tracks. They’re beautiful and majestic, their steps thoughtful and deceivingly quick. They’re like a dream when the foreground and the background shift in countering time-lapse speeds, something slows down and something speeds up and it’s disorienting. They’re mesmerizing to watch and that’s how eland move. The lord derby’s eland stands at almost eight feet tall, clocking mid 40mph speed, and can disappear in the thick stuff as if they were a ghost. I understood the privilege of having Erik personally guide for me. He did everything at CAWA for a long time, everything from maintenance to guiding. You had to in a place this remote. Erik knew that my day 19 was on the tail of two weeks of heavy filming. He took it upon himself to find me an eland and make sure that the barter was an even trade. We moved out into a neighboring savannah and bumped paths with another hunter. We found shade, poured coffee, and talked hunting. He had been hunting in CAR several times and all over Africa. CAR was always his favorite. It attracted the purists and the adventure seekers. And it wasn’t for everyone. Eland will kill you with their keen senses and stamina. Bongo will turn you into a nocturnal animal and drive you to the edge of sanity as each night in the blind comes up empty. But it was addictive. Red river hogs, hartebeest, buffalo, bushbuck, roan, waterbuck, giant forest hogs; in Chinko it was a hunter’s Valhalla. While the civil war in CAR’s capital continued, for the first time hunting in Central Africa was talked about in mainstream media. There was bad press, with individuals condemning hunters for hunting during a war(or even at all). The New York Times, and Human Rights Watch kicked around in the dog pile and threw insults at CAWA. The irony of the anti-hunting claim of hunter immorality, “hunting during a genocide”, was that CAWA in effect was securing the region. It provided a base for military intervention, support for biologists to do wildlife research, and employment opportunity for Central Africans living in rural poverty. This area was forgotten by the central government, yet CAWA was able to give Chinko a level of security that both the wildlife and communities needed. The sun was high and it was time to start moving again. We finished the coffee and gave farewells and good lucks.

Aarifa’s small hands clutched the yellow jerry can between her legs. Her forearms thin and taut with lined muscles, she waddled with an arched back carrying the 50 kg of water fetched from the nearby Mbari. Like the rest of the Mbororo women from Sudan, she was dressed in a colorful red and blue robe. She was 11 and nearly a woman. She set down the can and rested by her mother. They sat against handmade clay pots, wooden cots, and were cooled by the shade of a tarp. Their camp was like a gypsy’s or a yard sale of far-off goods. Everything they owned always came with them. Aarifa’s mother lifted her baby brother around her shoulder and kissed Aarifa’s forehead. Aarifa looked around and saw the rest of her sisters working and then heard the sound of a high pitched whistle. The cattle would obey her father like dogs. He was tall and wore a faded red keffiyeh to protect him from the sun. He looked back at Aarifa and smiled. She was his treasure. His smile faded as he wondered if he would always be able to protect her. Aarifa jumped at the gunshot. She heard our .22 crack the air with that distinguishable .22 slap, the sound trailing and dying into the trees. We were taking some guineas for the evening to pair with our gozo and iodined water. I began hearing the sound of cattle and men whistling, and for a moment I was transported back to Texas. But the men herding the cattle weren’t the cowboys that I grew up seeing in the Hill Country. Aarifa’s father walked forward along with his brother and we all greeted. “As-Salaam-Alaikum.” “Wa-Alaikum-Salaam.” One of the trackers knew Arabic and spoke on our behalf. I had spent significant time in North Sudan, a desert-like place that resembled Skywalker’s Tatooine, and it was very interesting seeing the iconic bits of Sudanese culture in a Central African forest. They were kind and welcoming and gave us milk. I saw Aarifa move behind her father as he held her hand while he spoke. The tracker listened to Aarifa’s father and then explained to him about the dangers of poaching, poisoning, and grazing. However, he offered that there was another way for Aarifa’s family. The Chinko Project developed a specific corridor for families, like Aarifa’s, to graze their cattle. It’s an attempt to protect the area, but to also remain sensitive to the Mbororo way of life. It’s common in Africa for war, famine, and disease to push people from their homes. You learn to shoulder other people’s burdens, but it becomes complicated when their plight infringes upon the sanctity of something else. Conversation slowed and we felt the natural moment to leave their family and move on. Everyone shook hands and I waved at Aarifa as she smiled back.

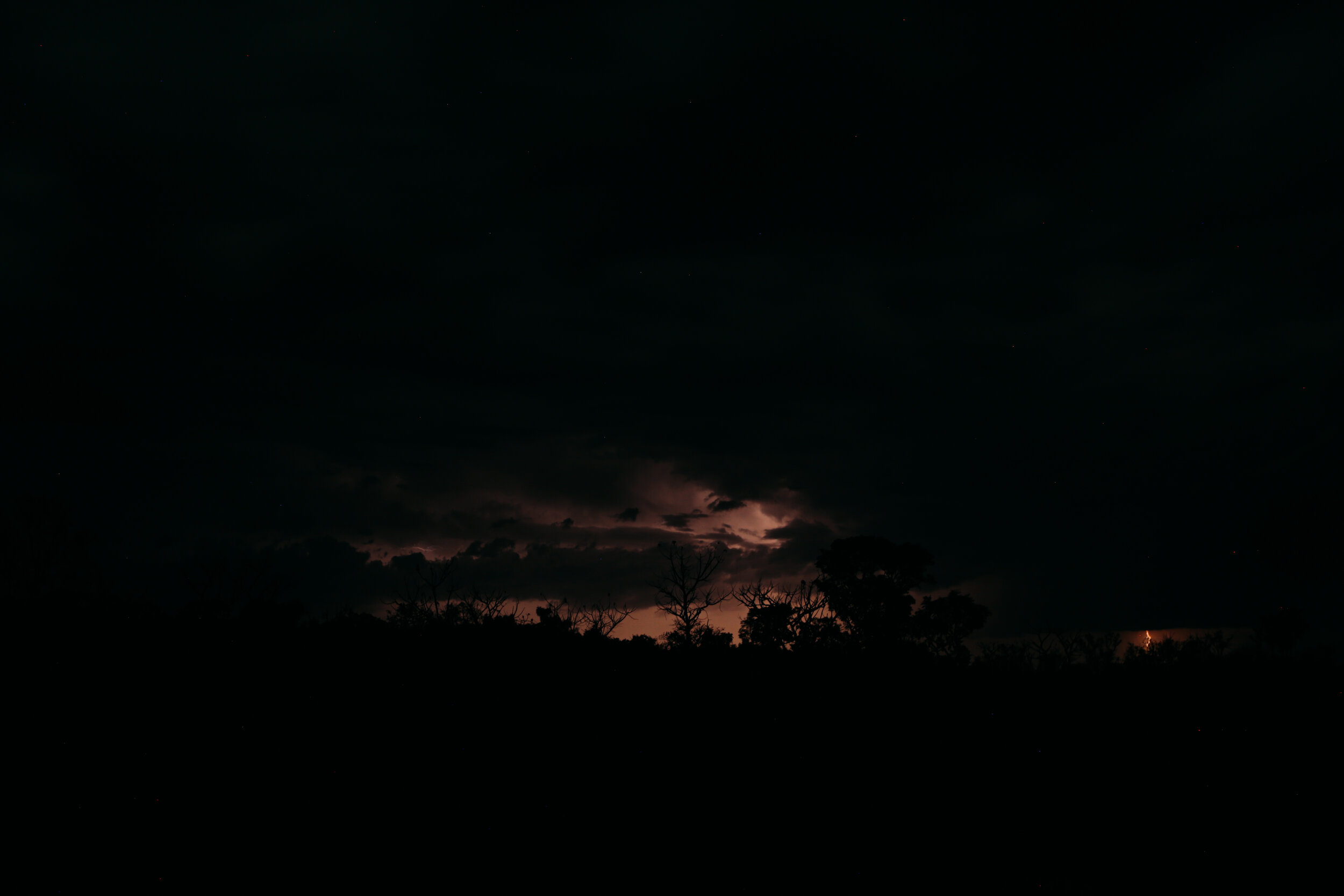

There was a palpable emptiness. Ghost town savannahs with varied sightings of warthog and baboons casted most of the shadow. The effects of poaching were clear in the wildlife absence. It was beyond 3pm at this point and we had recently jumped on a new eland track. It was the closest we ever came to taking a large bull. It was like they knew we were there, countering every one of our moves with precision, but only enough to leave room for false hope of a shot. We were moving through nearly impassable brush and the wind shifted. They vanished and I never saw another eland the rest of my time in Chinko. Before I could begin reflecting on what went wrong, the voice in my head was overcome with the sound of an aircraft passing nearby. Erik, the trackers, and myself peered up through salty sweat and saw a CV-22 Osprey moving above us and heading back for the Chinko airstrip. The LRA weren’t far and there were current troop movements pursuing them. Seeing an Osprey or any other surveillance aircraft wasn’t necessarily surprising. We cleared another batch of forest, but not before coming upon a fresh LRA camp. The insides of a waterbuck lay across the grass and its skinny legs sat on either side. A storm looked to be brewing and we decided to return to the airstrip. We arrived to see a few parked helicopters and an incoming 206 with a fresh batch of hunters. The hunters stepped off the plane and began taking pictures with their iPhones. Erik guided me over to a colonel from the UPDF where he sat under a thatched roof with maps lining the walls. Erik and the colonel began sharing intel and in the distance you could hear UPDF soldiers jogging the airstrip singing something in Lugandan. Erik’s men, his park rangers, would soon begin a grueling two month weed out. It was important to stay in comms with the UPDF since both patrols would be crossing in similar areas. A park ranger is defined as a person entrusted with protecting and preserving parklands. They’re men and women we give the earth to. We give them the earth and everything in it because we entrust what’s left to their stewardship and at times what calls them to lay down their lives. Patrols with African rangers consist of long treks through the bush, quiet nights under the stars, and all the while an unspoken, yet visible edge throughout the troops. Their enemy is almost invisible. The fear of something being near always left your guard up, but their consistent absence would create long periods of redundancy, slowness, and a false sense of peace. However, the calm moments could without warning snap. It takes staggering amounts of bravery to be a ranger. They’re heroes not just to the wildlife they protect, but to us all. The storm was nearly overhead and the sky’s gradient orange was turning into night. We left the UPDF base and headed back to the CAWA headquarters.

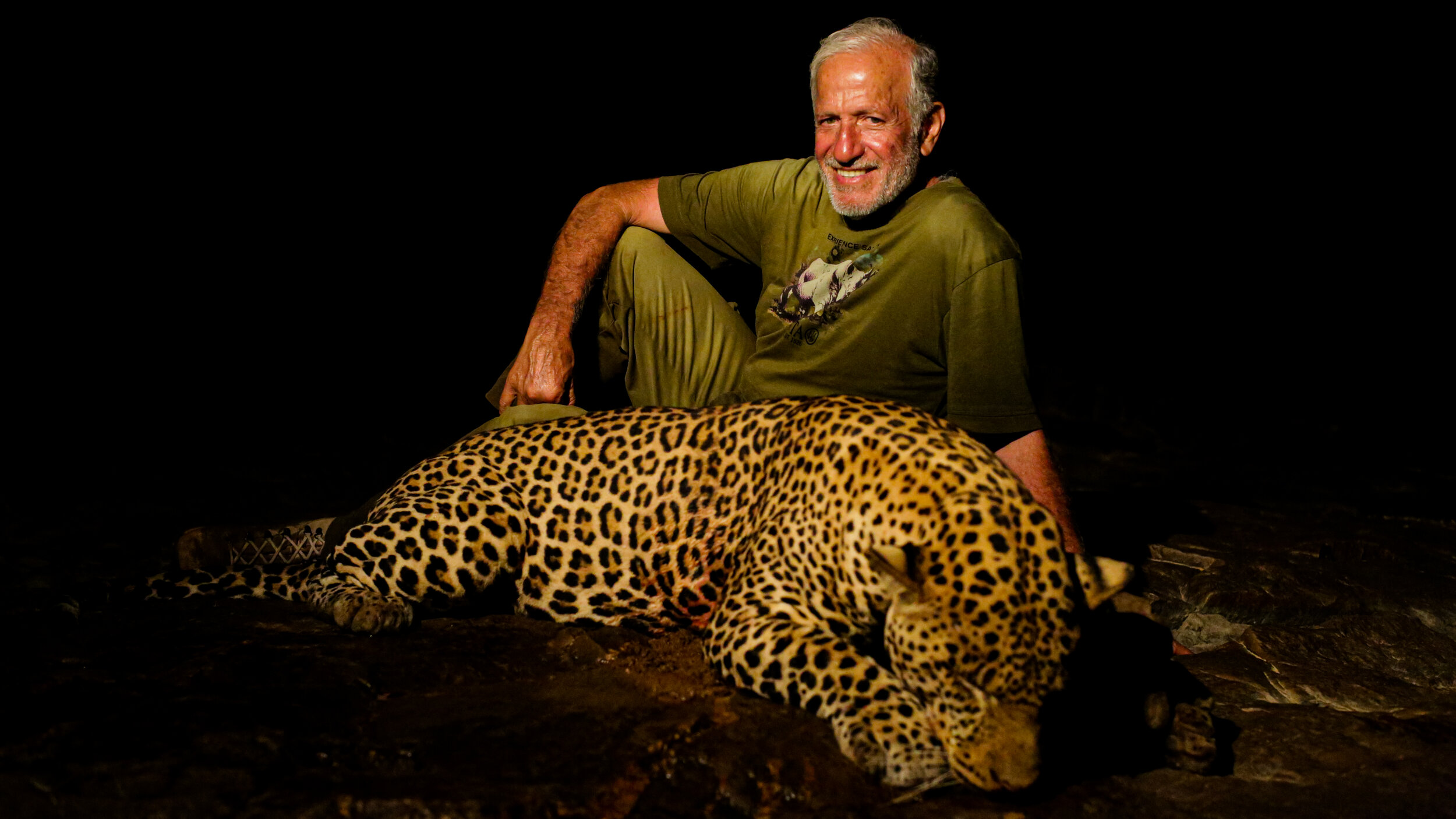

Back at HQ, a group of hunters sit and pass casual conversation. Servers move past the wall of docked rifles and deliver plates of fresh jams and warm crêpes. The open air dining room is lit by gas lamps and echoes what a four star hotel might look like. They consult with their guides on the day’s success or failure. “Le fromage,s’il vous plaît.” The befriended Russian passes a plate of brie and a half eaten baguette to his French neighbor. The Russian finishes his glass of vodka and nods to the Frenchman before parting ways. “Good luck tomorrow.” “Oui. Bon chance.” Everything started to feel like Homer’s Odyssey. In Chinko you pass through worlds. I took a smoke and a cup of tea outside while thunder and lightning rolled over the Mbari. It was night now. A biologist from The Chinko Project sat inside the adjoining brick shelter and thumbed through an electronic pile of camera trap photos. I could see over his shoulder and I felt a bit of hope as leopards, eland, and elephants lit the screen. In the stack were images of poachers as well, their overexposed black and white mug shots reminding us of the stark realities. This place was indeed mysterious and the land itself almost seemed alive. It knows that what lives here is precious and in its arms of forest and dark corners it offers protection. Maybe for that I could leave resolved having seen very little. I began hearing a steady drum and chanting voices through the trees. It was liturgical in its cadence and feral in its howls. The plaintive cries wailed in high, violent delight; starting low, rising in cheer, and going low again. Men were dancing and spinning in circles around something on the ground. They were feathered in branches and leaves, while the idol being tapped around in worship and in victory. A man had just returned from a hunt and was adorned in the foliage, like a baptism from the forest the African trackers covered his body in nature’s garments and hailed him a great warrior. Bound to a limb a leopard lay under the silhouettes of dancing shadows against the headlights. Lifeless and abreast to the ground, but beautiful and nearly blinding to look at with its holy presence. I reached the congregation of men and was passed a canteen of tequila. The leopard was raised from the dirt and pairs of men would take turns on either ends of the pole bouncing with a witch’s cavort. The leopard thrusted in the air and jigged his hips in a final dance. His spirit joined the men, the wild dogs of the forest that walked upright and growled and balled at the moon’s watching. The rain started and I could see a few stars through the night clouds. I wondered at everyone’s proximity: the poachers, the rebels, the Mbororo, the rangers, the hunters, and the center of their conflict, the one thing that connected all of them, the wildlife. I took it in one last time and retired to bed. Another day passes in a land that holds and evokes beauty. A land that sits at the helm of many, but belongs to no man.

Behind the Project

In 2014 I spent 2 months in the Central African Republic while individually commissioned by The African Parks Network, Icon Magazine, and The Chinko Project. My time was spent covering CAR’s illegal ivory poaching and the ongoing hunt for top members of the Lord Resistant’s Army. In the process I found myself in a world that was its own, unaware of its unique and temporal existence, I was fascinated by the sqewed utopia that became the Chinko Mbari Basin. Since writing this article, CAWA Safaris has closed down due to unsustainable poaching, The African Parks Network has assumed conservational governance, and the military entities have left to chase Kony in other No Man’s Land.

*Camera trap photos courtesy of Raffael Hikisch and Thierry Aebischer.

*Hunting footage courtesy of Christophe Morio.